ซูสีไทเฮา (慈禧太后) (ตอนที่ ๗) พระฉายาทิสลักษณ์สีน้ำมันแบบตะวันตกของซูสีไทเฮา โดย Katharine Carl

ซูสีไทเฮา (慈禧太后) (ตอนที่ ๗)

พระฉายาทิสลักษณ์สีน้ำมันแบบตะวันตกของซูสีไทเฮา โดย Katharine Carl

ภาพที่ได้รับการบูรณะและสร้างสรรค์ด้วย AI ภาพนี้ มาจากภาพต้นฉบับพระฉายาทิสลักษณ์สีน้ำมันแบบตะวันตกของ Empress Dowager Cixi วาดโดย Katharine Carl ในช่วงปี ค.ศ. 1903–1904 ทรงฉลองพระองค์ เฉิงอี (承衣) สีเหลืองจักรพรรดิ ประดับลวดลายปักรูปหัวหอม (onion-bulb motif) และอักษรมงคลจีน พร้อมเครื่องประดับไข่มุกล้ำค่า และ “เสื้อคลุมไข่มุก” อันเลื่องชื่อ

แคทเธอรีน คาร์ล กับกรอบจารีตของราชสำนักชิง

คำบันทึกของแคทเธอรีน คาร์ล สะท้อนข้อจำกัดที่เธอต้องเผชิญอย่างชัดเจน:

“ข้าพเจ้าจำต้องปฏิบัติตามขนบธรรมเนียมที่สืบต่อกันมาหลายศตวรรษในทุกรายละเอียด ภาพต้องปราศจากเงาและแทบไม่มีมิติ ทุกอย่างต้องสว่างเต็มที่จนไร้ความนูนลึกและอารมณ์แบบจิตรกรรม… ข้าพเจ้าต้องต่อสู้กับความรู้สึกต่อต้านภายในอยู่นาน ก่อนจะยอมรับสิ่งที่หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้”

— With the Empress Dowager of China (ค.ศ. 1905)

คาร์ลระบุว่า ทั้งข้าราชการในราชสำนักและซูสีไทเฮาเอง ต่างกดดันให้เธอปฏิบัติตามจารีตการสร้างภาพเหมือนแบบจีนอย่างเคร่งครัด ได้แก่ การใช้แสงแบนราบ รายละเอียดสูง ไม่มีเงาดรามาติก และไม่เปิดพื้นที่ให้จินตนาการเชิงศิลปะ แม้จะเป็นภาพวาดสีน้ำมันแบบตะวันตก ก็ยังต้องทำหน้าที่เช่นเดียวกับภาพราชสำนักจีน

เมื่อวันที่ 19 เมษายน ค.ศ. 1904 ขณะภาพใกล้เสร็จสมบูรณ์ ได้มีการถ่ายภาพบันทึกภาพวาดนี้โดย Xunling ช่างภาพหลวงชาวแมนจูผู้ได้รับการศึกษาในต่างประเทศ เหตุการณ์นี้—การถ่ายภาพภาพวาดตะวันตกของซูสีไทเฮาภายในพระราชสำนัก—สะท้อนความตึงเครียดระหว่างจารีตดั้งเดิม ความทันสมัย และการควบคุมภาพแทนอำนาจในช่วงปลายราชวงศ์ชิงได้อย่างชัดเจน

________

จิตรกรตะวันตกกับการ สร้างภาพลักษณ์ของซูสีไทเฮา ในกรอบความคิดแบบใหม่

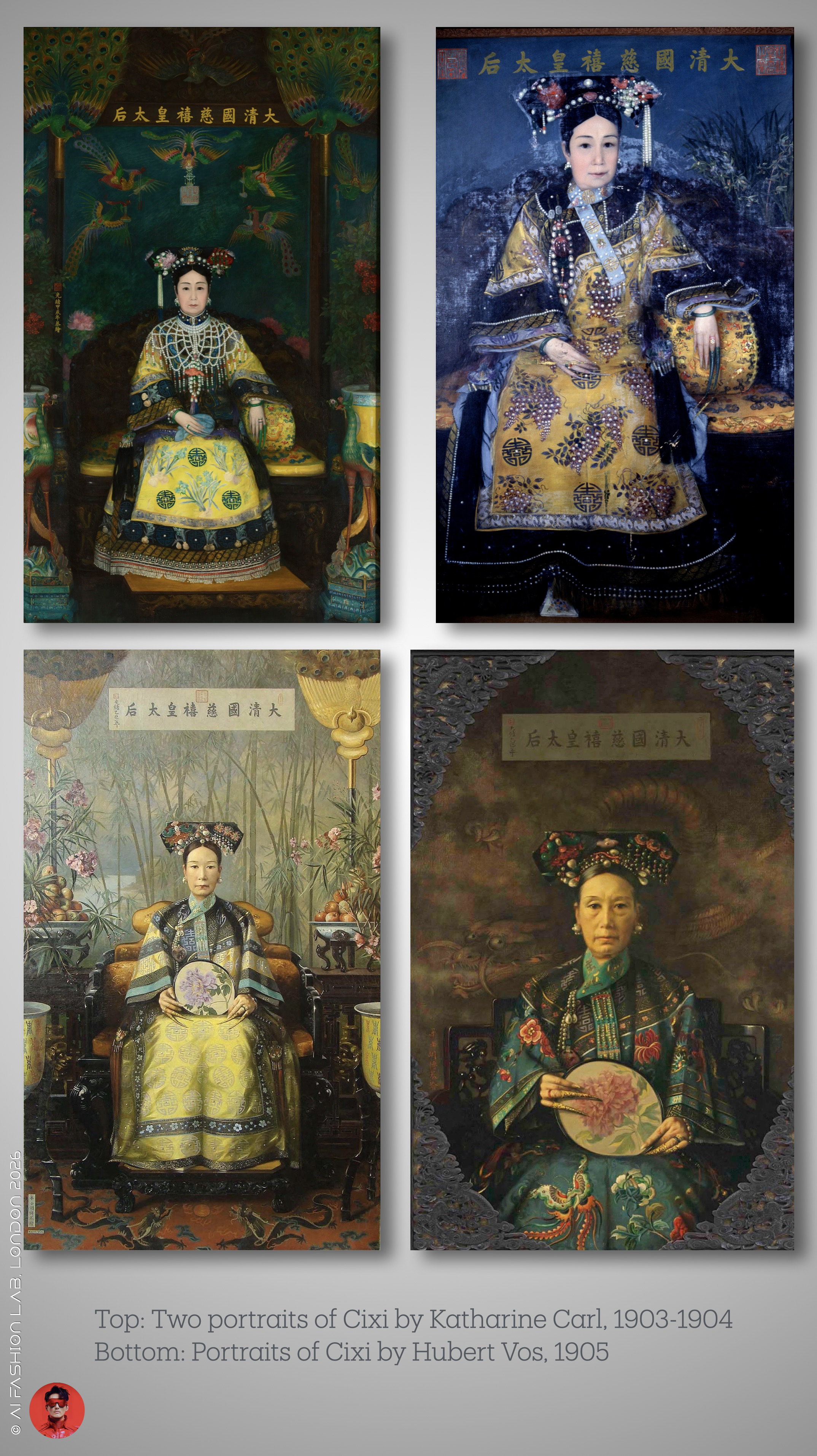

นอกเหนือจากชุดภาพถ่ายของซุนหลิงแล้ว จิตรกรตะวันตกสองคนมีบทบาทสำคัญในการสร้างภาพลักษณ์ใหม่ของซูสีไทเฮาในสายตาชาวอเมริกัน ได้แก่

Katharine Carl ผู้สร้างภาพเหมือนขนาดเท่าคนจริงในช่วงปี ค.ศ. 1903–1904

Herbert Vos จิตรกรลูกครึ่งดัตช์–อเมริกัน ซึ่งผลงานบางชิ้นถูกรวบรวมไว้ที่พิพิธภัณฑ์ Fogg Art Museum มหาวิทยาลัยฮาร์วาร์ด

ในปี ค.ศ. 1903 Sarah Pike Conger ภริยาของทูตสหรัฐฯ ประจำกรุงปักกิ่ง ได้กราบทูลขอพระราชานุญาตให้ว่าจ้างภาพวาดสีน้ำมันขนาดใหญ่ เพื่อนำไปจัดแสดงในงาน World’s Fair ที่เซนต์หลุยส์ ในปี ค.ศ. 1904 ด้วยเหตุผลว่า “เพื่อให้ชาวอเมริกันได้เห็นว่าสมเด็จพระจักรพรรดินี พระพันปีหลวง แห่งจีนเป็นสตรีที่งดงามเพียงใด” คาร์ลจึงพำนักอยู่ในพระราชวังฤดูร้อนใหม่เป็นเวลานานเกือบหนึ่งปีเพื่อสร้างผลงานนี้

ภาพวาดที่แล้วเสร็จมีขนาดใหญ่กว่า 112 × 64 นิ้ว ถูกใส่กรอบไม้แกะสลักขนาดมหึมาซึ่งเชื่อกันว่าซูสีไทเฮาทรงมีส่วนออกแบบ ถูกส่งไปยังสหรัฐฯ พร้อมคณะข้าราชการแมนจู และจัดแสดงในตำแหน่งสำคัญของหอศิลป์ภายในงาน หลังงานสิ้นสุด ภาพนี้ถูกมอบให้แก่ Theodore Roosevelt และต่อมาถูกโอนไปยังสถาบันสมิธโซเนียน ควบคู่กับการบรรยายและหนังสือของคาร์ล กระบวนการทั้งหมดนี้คือการจัดวางภาพตัวแทนของ “สตรีผู้ยิ่งใหญ่แห่งจักรวรรดิจีน” ในสังคมอเมริกันอย่างเป็นระบบ

________

ระเบียบการแต่งกายกับอัตลักษณ์จักรวรรดิ

ในราชวงศ์ชิง (ค.ศ. 1644–1912) เครื่องแต่งกายเป็นกลไกสำคัญในการกำหนดอัตลักษณ์ ลำดับชั้น และอำนาจ โดยถูกควบคุมด้วยพระราชกฤษฎีกาอย่างเคร่งครัดตาม ฐานะ โอกาส และเพศ สตรีในราชสำนักปฏิบัติตามลำดับชั้นการแต่งกายที่แบ่งชัดเจนระหว่างเครื่องทรงพิธี เครื่องทรงกึ่งพิธี และเครื่องแต่งกายไม่เป็นพิธีการ

ในโอกาสพิธีการสำคัญ สตรีจะสวม ฉาวฝู (朝服) ซึ่งเป็นฉลองพระองค์แขนยาว ปลายแขนทรงกีบม้า (hoof-shaped cuffs) ปักหรือทอด้วยสัญลักษณ์จักรวรรดิและลวดลายมงคลอย่างเข้มงวด เครื่องทรงประเภทนี้เน้นการสื่อสารระเบียบจักรวาลและความชอบธรรมของราชวงศ์ มากกว่ารสนิยมส่วนบุคคล

สำหรับบริบทไม่เป็นพิธีการ เครื่องแต่งกายหลักมีสองประเภท คือ ฉางอี (常衣) และ เฉินอี (衬衣) ความแตกต่างสำคัญอยู่ที่โครงสร้างด้านข้าง โดย ฉางอี มีผ่าข้างทั้งสองด้าน ช่วยให้เคลื่อนไหวได้สะดวก ขณะที่ เฉินอี ปิดทึบด้านข้าง ทำให้ทรงเสื้อดูนิ่งและจำกัดการเคลื่อนไหว ฉลองพระองค์ในพระฉายาทิสลักษณ์นี้มีผ่าข้างชัดเจน จึงควรจัดอยู่ในประเภท ฉางอี แม้ในเอกสารพิพิธภัณฑ์บางแห่งจะเรียกรวมภายใต้คำว่า เฉิงอี

________

ชุด ฉางอี กับมารยาทราชสำนักฝ่ายใน

ฉางอี เป็นชุดกระโปรงยาวและบางครั้งประดับด้วยผ้าพันคอที่เหมือนกับริบบิ้นยาว เพื่อรักษาความสุภาพและไม่เปิดเผยผิวหนังมากเกินควร แม้ถูกจัดเป็นชุดแบบ “ไม่เป็นพิธีการ” แต่เครื่องแต่งกายเหล่านี้เปิดพื้นที่ให้สตรีชั้นสูง—โดยเฉพาะผู้มีอำนาจสูงสุด—ถ่ายทอดความสวยงามของงานปักที่ละเอียดอ่อน และสีสันที่สวงามของผ้าไหม และภาษาของสัญลักษณ์ต่างๆที่ปรากฎบนชุดได้มากกว่าชุดแบบพิธีการ

สำหรับซูสีไทเฮา ฉางอี กลายเป็นสื่อที่เต็มไปด้วยความหมายจากลวดลายปัก ซึ่งเป็นสัญลักษณ์การแสดงอำนาจของพระองค์ สำหรับฉลองพระองค์ที่ทรงในพระฉายาทิสลักษณ์นี้ สีเหลืองจักรพรรดิซึ่งปกติสงวนสำหรับองค์จักรพรรดิ ตอกย้ำถึงสถานะผู้ที่กำอำนาจในราชสำนักโดยพฤตินัยของพระองค์

________

การออกแบบและการปักไหม ฉางอี

การตัดเย็บชุดแบบ ฉางอี และการปักชุดด้วยลวดลายต่างๆด้วยเส้นไหมคุณภาพสูงเป็นกระบวนการที่ซับซ้อนและยาวนาน กระบวนการทั้งหมด เริ่มจากการว่าจ้างช่างเขียนลายราชสำนักออกแบบลวดลายทั้งหมด เพื่อนำเสนอให้ผู้ที่ส่วมใส่พิจารณาและอนุมัติ เมื่อผ่านความเห็นชอบ ลวดลายจะถูกวาดลงบนผ้าไหมด้วยผงถ่านหรือชอล์ก จากนั้นจึงเขียนเส้นกำกับลงบนผืนผ้าเพื่อเป็นแนวทางให้ช่างปัก

งานปักระดับสูงต้องอาศัยทักษะอย่างยิ่ง เส้นไหมหนึ่งเส้นสามารถแยกออกเป็น 10–48 เส้นย่อย แล้วปักซ้อนเป็นชั้น ๆ ด้วยเฉดสีหลากหลาย เพื่อสร้างมิติ แสง และความเคลื่อนไหว งานชั้นเลิศอาจต้องใช้ช่างฝีมือถึง หกคน และใช้เวลาหลายปี จึงสะท้อนทั้งความมั่งคั่ง เวลา วินัย และองค์ความรู้ที่สั่งสมจากรุ่นสู่รุ่น

________

ลาย “หัวหอม”: ความอุดมสมบูรณ์ การคุ้มครอง และความต่อเนื่องของราชวงศ์

ลวดลายหลักบนฉลองพระองค์นี้เป็น ลายหัวหอม ซึ่งมีรากฐานจากศิลปะพุทธและเอเชียกลาง เข้าสู่ราชสำนักชิงผ่านการอุปถัมภ์ของจักรพรรดิ รูปทรงซ้อนชั้นและพองตัวของหัวหอมสื่อถึง ความอุดมสมบูรณ์ การปกป้อง และพลังชีวิตที่ต่อเนื่อง ในบริบทของเครื่องแต่งกายสตรีชั้นสูง ลายนี้มีนัยสำคัญเป็นพิเศษ ชั้นต่างๆที่ซ้อนกันของหัวหอม สื่อถึงการโอบอุ้มและความทนทาน เปรียบพระวรกายของซูสีไทเฮาเป็นแกนกลางที่คุ้มครองจักรวรรดิ

________

เหตุใดจึงแปลภาพวาดให้เป็นภาพถ่าย

การแปลภาพวาดสีน้ำมันตะวันตกภาพนี้ให้กลายเป็นภาพถ่ายเสมือนจริง ช่วยให้เราเห็นรายละเอียดของชุด ได้ชัดเจนยิ่งขึ้น และเปิดพื้นที่ให้ศึกษาแฟชั่นแบบราชสำนักชิง ตั้งแต่การใช้สี การปัก เครื่องประดับ ไปจนถึงการใช้วัสดุต่างๆ ในที่นี้ AI ไม่ได้ถูกใช้เพื่อแทนที่ความสำคัญของภาพต้นฉบับ หากแต่เป็นเครื่องมือเพื่อ ทำให้ภาพมีความชัดเจน และเหมาะสมสำหรับการศึกษาประวัติศาสตร์แฟชั่น

ที่มา: Visualizing Cultures, MIT – Empress Dowager Cixi

_______________________

Western Painted Portrait of Empress Dowager Cixi by Katharine Carl

This AI-restored and colourised image is derived from an original Western oil-painted portrait (พระฉายาทิสลักษณ์) of Empress Dowager Cixi, painted by Katharine Carl between 1903 and 1904. Cixi is depicted wearing an imperial-yellow chengyi (承衣), an informal court robe of imperial rank, richly embroidered with onion-bulb motifs and auspicious Chinese characters. The ensemble is completed with her renowned pearl jewellery and the legendary pearl cape, together forming a powerful visual statement of authority, wealth, and symbolic sovereignty within the late Qing imperial court.

Katharine Carl and the Constraints of Qing Court Convention

Katharine Carl’s own writings reveal the strict limitations under which she worked:

“I was obliged to follow, in every detail, centuries-old conventions. There could be no shadows and very little perspective, and everything must be painted in such full light as to lose all relief and picturesque effect… I had many a heartache and much inward rebellion before I settled on the inevitable.”

— With the Empress Dowager of China (1905)

Carl noted persistent pressure from both court officials and Cixi herself to conform rigorously to Chinese portrait conventions: flattened lighting, maximum clarity of detail, the absence of dramatic shadow, and no room for personal artistic fantasy. Even though the medium was Western oil painting, the image was required to function in the manner of a traditional Chinese imperial portrait.

On 19 April 1904, as the painting neared completion, it was ceremonially photographed by Xunling, a Manchu court photographer educated abroad. This act—photographing a Western oil portrait of the Empress Dowager within the palace—captures with particular clarity the late-Qing tension between tradition, modernity, and the controlled production of imperial imagery.

Western Painters and the Re-Making of Cixi’s Image

Beyond Xunling’s photographic series, two Western artists played key roles in reshaping Cixi’s image for American audiences:

Katharine Carl, who produced a life-size portrait of Cixi between 1903 and 1904.

Herbert Vos, whose 1905 portraits later entered the collection of Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum.

In 1903, Sarah Pike Conger, wife of the American envoy to Beijing, sought imperial permission to commission a large oil painting for display at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, stating that it would allow “the American people to form some idea of what a beautiful lady the Empress Dowager of China is.” Carl consequently resided in the New Summer Palace for nearly a year to complete the commission.

The finished painting—measuring over 112 × 64 inches—was mounted in an enormous carved wooden frame said to have been designed with Cixi’s input, shipped to the United States accompanied by Manchu officials, and given a prominent place in the exposition’s art gallery. After the fair closed, the portrait was presented to Theodore Roosevelt and later transferred to the Smithsonian Institution. Together with Carl’s lectures and memoir, this carefully orchestrated process established a public image of Cixi as the “great lady” of imperial China in American society.

Dress Regulation and Imperial Identity

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), dress functioned as a primary mechanism for defining identity, hierarchy, and authority. Imperial decrees regulated attire according to status, occasion, and gender, and women of the court adhered to a clearly articulated sartorial hierarchy distinguishing ceremonial, semi-ceremonial, and informal dress.

For formal occasions, court women wore chaofu (朝服): long-sleeved robes with distinctive hoof-shaped cuffs, densely embroidered or woven with imperial and auspicious symbols. These garments were visually rigid and ritually codified, designed to communicate cosmic order and dynastic legitimacy rather than individual taste.

In informal contexts, women wore two principal robe types: changyi (常衣) and chenyi (衬衣). The crucial structural difference lies in the side seams: the changyi has slits on both sides, allowing greater freedom of movement, while the chenyi is closed at the sides, producing a more restrained silhouette. The robe shown in this portrait clearly displays side slits and should therefore be classified as a changyi, even though some museum catalogues refer to it more broadly as chengyi.

The Changyi Ensemble and Female Court Decorum

The changyi was never worn alone. It formed part of a carefully regulated ensemble including a long skirt and, at times, a long neck ribbon or scarf, ensuring propriety and avoiding excessive exposure of the body. Although classified as informal, such garments offered elite women—especially those at the apex of power—greater scope for elaborate embroidery, refined colour palettes, and symbolic expression than was possible in strictly ceremonial attire.

For Cixi, the changyi becomes a vehicle of authority. The imperial yellow ground, normally reserved for the emperor, underscores her position as the de facto ruler, while the density and sophistication of the embroidery signal command over time, labour, and material resources.

Designing and Embroidering a Silk Changyi

Producing a high-quality silk-embroidered changyi was an exceptionally complex and time-consuming process. It began with the commissioning of a court artist to design the complete decorative programme, which was then submitted to the wearer for approval. Once approved, the design was transferred onto the silk ground using charcoal or chalk, and the outlines were redrawn directly onto the fabric to guide the embroiderers.

Elite Qing embroidery required extraordinary skill. A single silk thread could be split into 10 to 48 finer filaments, layered in successive stitches with subtly varied colours to create depth, tonal transition, and surface movement. Completing a robe of the highest quality could involve up to six craftspeople working over several years, embodying not only wealth but also accumulated time, discipline, and intergenerational knowledge.

Onion-Bulb Motifs: Abundance, Protection, and Dynastic Continuity

The principal embroidered motif on this robe is the onion-bulb form, derived from Buddhist and Central Asian visual traditions and incorporated into Qing court art through imperial patronage. Its layered, swelling structure symbolises abundance, protection, and the continuity of vital force.

In the context of elite female dress, the motif carries particular resonance. The concentric layers evoke containment and endurance, aligning Cixi’s body with the empire imagined as a protected, generative core. The motif’s repetition across the robe transforms the garment into a continuous visual field of auspicious prosperity rather than a narrative image.

Why Translate Paintings into Photographs?

Translating this Western oil painting into a realistic photographic image allows the details of dress to be seen with greater clarity and opens new avenues for studying Qing court fashion—from colour hierarchy and embroidery to jewellery and material choice. Here, AI is not used to replace the authority of the original artwork, but as a tool to clarify and render the image more legible for the study of fashion history.

Source: Visualizing Cultures, MIT – “Empress Dowager Cixi”

_______________________

เรียนเชิญกด Subscribe ได้ที่ลิงก์นี้ครับ เพื่อร่วมติดตามงานสร้างสรรค์ต้นฉบับ งานวิจัยประวัติศาสตร์แฟชั่น และผลงานอนุรักษ์มรดกวัฒนธรรมด้วยเทคโนโลยี AI ของ AI Fashion Lab, London ซึ่งมุ่งตีความอดีตผ่านมิติใหม่ของการบูรณะภาพ การสร้างสรรค์ภาพ และการเล่าเรื่องด้วยศิลปะเชิงดิจิทัล 🔗 https://www.facebook.com/aifashionlab/subscribe/

#aifashionlab #AI #aiartist #aiart #aifashion #aifashiondesign #aifashionstyling #aifashiondesigner #fashion #fashionhistory #historyoffashion #fashionstyling #fashionphotography #digitalfashion #digitalfashiondesign #digitalcostumedesign #digitaldesign #digitalaiart #ThaiFashionHistory #ThaiFashionAI #thailand #UNESCO